by Estelle Baroung Hughes

I. Conceptualizing peace in international education

Peace is a spiral of hope that starts at the level of self and spreads out towards others and the world. Because peace both grounds and de-centers us, it can be compared to a seed of beauty that grows within us and produces healing fruits that turn chaos into calm, volatility into stability, and pessimism into action and gratitude. Education for peace comes with a question and a tremendous challenge. How are we concretely centering peace in spaces of privilege? Reflection, intentionality and action are needed beyond words.

Peace is not quietism. It is not the bliss provided by ignorance or the silence produced by pressure and oppression. Peace is the opposite of injustice and destruction. Hence the mottos, no justice, no peace, or no sustainability, no peace. But it is possible and usual to plant the seeds of peace in imperfect soil. That is when peace takes the shape of hope for peace, healing, liberation, nonviolence, resilience, forgiveness or a growth mindset.

The world we live in is in desperate need of peace. Around 150 armed conflicts are costing tens of thousands of lives every year. Polarization and nationalism, the climate crisis and the AI revolution make insecurity and unpredictability rife. How do we exist in peace and for peace in the midst of such chaos? What does that look like for international education leaders?

As a concept, an ideal and a set of educational and instructional practices, International Education started after World War I in Switzerland and Japan. The focus on peace led the first international schools towards the creation of supra-national curricula, centering world history, constructivism and anti-war values so that learning eventually prevents wars. Today, war is more than ever in the picture. International schools have also become tremendously diverse, thanks to the expansion of this professional branch made of a growing number of international schools, accreditation bodies and professional development organizations. There is a striking heterogeneity of cultural fabric, socio-economic status and philosophical outlook in the schools lumped together under the umbrella of international education. Therefore, from inner peace- encompassing mindfulness, resilience, gratitude and more- to world peace- oscillating between the preservation of international dialogue and the protection of our planet- schools that promote education for peace have many potential areas of focus.

To me, peace is Ubuntu, an African philosophy. Ubuntu is the acknowledgement of our interconnectedness as humans and with nature. ‘I am because we are’ is the conceptual message of this philosophy. Ubuntu is about collective responsibility, generosity and respectful communities. Ubuntu has many names and faces: terranga in Senegal, Umoja in Kenya, Diatigui in Mali and many more names across Africa. But Ubuntu also has an edge: South Africa, a country where Ubuntu is a household cultural reference, gave this ideal a more powerful reach through the anti-apartheid liberation movement. Ubuntu does potentially mean sacrifice and struggle, something that is difficult to sell to the international school community and a topic that deserves its own article.

At the intersection of international education leadership and peace-making, there is the commitment to build care: for self, for others and for the planet. This entails a strong commitment to custodianship, wellbeing and supporting sustainability around school, without ignoring the importance of creating brave spaces for respectful discomfort and disagreement.

Challenging times come when external wars make it into the school community or when pain, injustice and conflict arise. In these times, the role of the ubuntu-minded school leader is to decenter themselves, listen to all stakeholders and act in consideration of the equal value of each human being. This is when civic conversation matters the most, which is teaching students the value of dialogue, perspective and listening to build community and a deeper understanding of the world around them.

In peace-based leadership, a school leader pays attention to more than trains running on time. Si vis pacem, para pacem. If you want peace, prepare/scaffold it (as opposed to the original Latin phrase that says ‘if you want peace, prepare war’). It is outside of tensions that the ubuntu-minded leader cultivates connection and gets people together through connecting protocols, team building practices, assemblies, think tanks, task forces, student government, advisory groups, mediation circles, etc. It is important to support social and emotional learning, global affairs courses, and environmental projects in a serene environment. Prevention of conflict, propaganda, microaggressions, prejudice, violence and even littering works better when children internalize the right values outside of a conflictual situation. Education for Peace sometimes involves hard topics, like a deep reflection on how genocides start and develop. I believe that the awareness of what is happening in the world must be coupled with case studies from the past. Teaching History is a key part of learning about social justice and political power. Maintaining this subject in the curriculum and activating its reflective and peace-making potential is impactful leadership.

II. Peace domains in international education

The word peace might not feature in the mission, vision or charter of your school, but peace is a wide umbrella with multiple connotations and manifestations that we will call ‘domains’. In this article, peace domains are some of the prominent educational ideals and constructs that relate to inner peace, collective peace and world peace. They include, in no particular order: wellbeing, conflict resolution, global citizenship, intercultural education, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Justice (DEIJ), multilingualism, sustainability and leadership.

The table below proposes some areas of focus, presented as ‘tools’ for each peace domain, breaking down the reflection between inner peace, collective peace, and world peace. While reading this table, mentally highlight the domains and tools where your leadership and awareness are strong and others that may need your attention and focus as a leader.

| Peace domains | Tools for inner peace | Tools for collective peace | Human skills for world peace |

| Wellbeing | Mindfulness Mental Health Education Social Emotional Learning | Custodianship(Child protection) Community and team norms A culture of Kindness & collaboration | Balance Happiness Humaneness |

| Conflict-Resolution | Centering kindness& empathy Social Emotional Learning | Listening Circles Mediation teams Restorative approaches | Community building Active listening Altruism |

| Global Citizenship | Local & Global educational perspectives international experiences | Community engagement Civic conversation Peacebuilding & international relations platforms | International-mindedness Social impact: think global, act local Critical thinking |

| Intercultural education | Cultural mirrors and windows in the curriculum (to understand self & others) | Ubuntu (highlighting the interconnectedness of people and cultures) | Self-Awareness Open-mindedness Curiosity |

| Diversity Equity, Inclusion & Justice | Safety from discrimination Self-advocacy Belonging | Inclusive education Representation Indigenous connections | Mental liberation Intersectional understanding of the world Post-colonial perspectives |

| Multilingualism | Home language learning Cultural enrichment | Cultural exchanges | Cultural literacy(knowledge and understanding of multiple cultures) |

| Sustainability | Learning in and with nature Food literacy Knowledge of Indigenous plants | Sustainability as a shared mission & vision | Environmental stewardship |

| Leadership | Political and ethical education Self-actualisation Sense of purpose | ‘Nothing about us without us’: relevant stakeholders involved in decision-makingand change management | Moral compass Inclusivity Inspiring & driving change |

Speaking peace

Building on peace domains awareness, peace-centered leadership ‘speaks peace’ in other words, makes peace visible around school. In every school I have led, we have celebrated the International Day of Peace in September. In the Northern hemisphere, the day comes early enough in the school year to function as a north star for the year to come. In my view, an effective celebration of peace has 3 key ingredients:

- Bringing the whole school community together, students, teachers, administration, staff and parents. Unity and participation are powerful expressions of peace.

- Re-affirming the school’s values and linking them to the ideal of peace is an important challenge for a school leader.

- Opportunities to reflect critically on challenges against peace at individual, social and global levels. This is better done in well-scaffolded and normed conversations led by educators.

III. Ubuntu as a strategic approach to implementing peace-based leadership

‘Alone we go fast, together we go far’. This African proverb means that success is directly linked to how we federate people. That is the spirit of Ubuntu.

Ubuntu-minded leadership

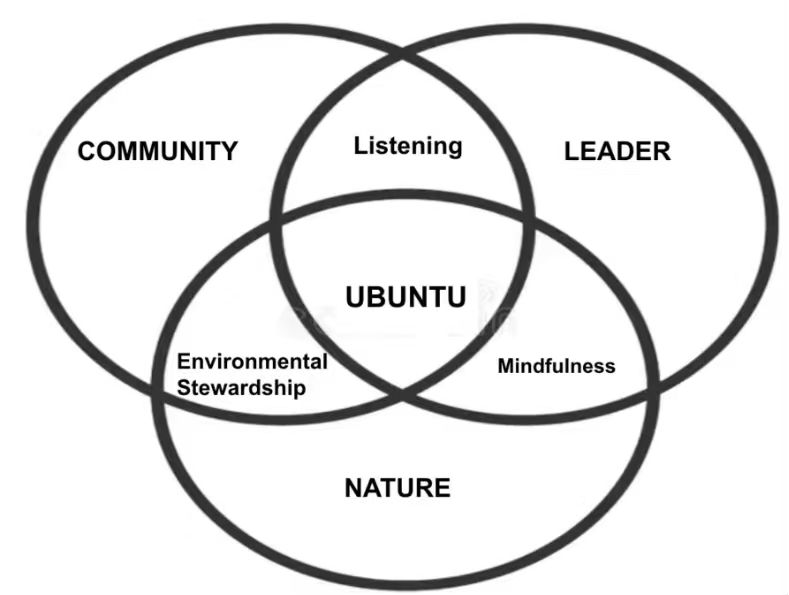

The diagram shows key priorities for an Ubuntu-minded leader:

- Listening: effective channels of communication, disclosure, and whistleblowing matter. Beyond that systematic approach, it is the skill of listening to each other, dialoguing interculturally and interpersonally that enhances ubuntu. This is something leadership should aim to develop and train in students and staff.

- A focus on environmental stewardship or sustainability. Ubuntu acknowledges what we owe to our environment. Through rituals like libation, many African cultures acknowledge that the ancestors are now one with nature. So let’s learn about and honour nature at school as a source of food, medicine, shelter and beauty.

- Mindfulness. This means understanding the need we have to spiritually connect and to just: be. Mindfulness can also become collective through professional rituals, retreats and team building that soften professional pressures. We are more productive and more engaged when work provides these peaceful spaces.

Conclusion

Today’s political, environmental and technological context calls for approaches to education for peace that do not rely on feel-good factors only. Peace-based leadership is complex and multifaceted. Nurturing individual wellbeing within the institution comes first. Then comes belonging as collective peace. Belonging is supported by interpersonal and intercultural dialogue at school, helping people adapt to each other and avoiding the domination of louder voices. School communities might not have the power to end wars and single-handedly save the planet, but we can orchestrate aspirational practices to inspire our students to do right by humanity and the planet when their time to lead the world comes. A very powerful moment in my career was the commemoration of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis at school in the presence of the Rwandan ambassador and the Senegalese author Boubacar Boris Diop, who wrote The Book of Bones. International students were analysing a Senegalese author’s book on Rwanda, in the presence of a representative of the people who were affected. This event, to me, created a powerful circle of peace, illustrating that we are each other’s keepers and dialogue generates the deepest understanding of what peace looks and feels like. Curriculum and teachers’ vision are key to creating this culture. School leaders should therefore consider the educators’ vision for peace when recruiting them. We also need to support this type of work and even model it. That is why I have launched the writing competition ‘Peace You have My Word’ that offers students around the world a platform to express what peace means to them. I take this opportunity to thank our sponsors (Initiatives for Change, ELMLE, TIE, Innustame, Educational Aspirations) and all the jury members who select laureates every year.

Last but not least, a peace-minded leader constantly keys in with the person in the mirror, asking: “Am I being aligned with my values as an educator and a school leader”?

My references and resources

● Community engagement and Environmental stewardship (3 [auto]biographies):

Maathai, Wangari. Unbowed: A Memoir. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006

Toole, David. Love Made Me an Inventor: The Story of Maggy Barankitse—Humanitarian, Genocide Survivor, Citizen without Borders. Orbis Books, NY, 2025.

Tutu, Desmund. No Future Without Forgiveness- Double day New York, 2000

● Language and liberation:

Ngũgĩ wa Thiongʼo. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. James Currey, 1986

● Story-telling bank: https://www.peacetalks.net/stories/

● Value-based International education (2 open access articles):

Gardner-McTaggart, A., Bunnell, T., Resnik, J., Tarc, P., & Wright, E. “Can the International Baccalaureate (IB) make a better and more peaceful world? Illuminating limits and possibilities of the International Baccalaureate movement/programs in a time of global crises.” Globalisation, Societies and Education, vol. 22, no. 4, 2024, pp. 553-562. 10.1080/14767724.2023.2252435

Hughes, C. Addressing violence in education: From policy to practice. Prospects 48, 23–38 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-019-09445-1

Estelle Baroung Hughes, Middle School Division Head, French International School of Oregon, USA

LYIS is proud to partner with WildChina Education