by Alissa Gouw

Knowledge as Assets in Schools

During one of the Parent-Student-Teacher Conferences (PSTC) at my school, one parent highlighted a veteran teacher who excelled at creating a supportive atmosphere during their conference. This teacher helped the parent and child easily understand the child’s progress and develop a clear plan for moving forward. Interestingly, all teachers used the same school-provided template to guide their conversations during the PSTC. So what made this teacher stand out from the rest?

The answer lies in their experiential knowledge-built over years of working closely with families. This knowledge is deeply embedded in their practice and exists in their mind and actions. The question then becomes: how can this valuable knowledge be brought to the surface, shared, and learned by others? In other words, how can we transform the knowledge into something visible that can be shared and learned by the entire school community?

The Role of Tacit and Explicit Knowledge in Schools

The expertise held by the veteran teacher is an example of tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is deeply personal and difficult to articulate or formalize. It consists of subjective insights, intuitions, and instincts and is closely connected to actions, routines, procedures, and emotional or value-based commitments (Nonaka et al., 2000). While tacit knowledge is challenging to share directly, it can be made accessible to others by transforming it into explicit knowledge. Explicit knowledge refers to knowledge that can be clearly expressed and documented using formal, systematic language (Nonaka et al., 2000).

The transformation of tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge will support the knowledge creation process that is very important for schools that want to be learning organizations. Senge (1990) defines learning organizations as “organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free…” Collective aspirations can be set free when tacit knowledge is shared and made explicit. This will allow teachers to learn from one another and build on each other’s experiences. This process helps schools curate a culture of collaboration, reflection, and growth, where people are not just working in isolation but are learning together as a community. The next question is: What is the effective framework to guide the process of converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge?

SECI Model as the Framework for Knowledge Creation

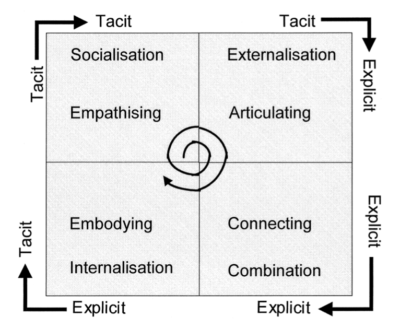

The SECI model that was introduced by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) stands for four stages involved in knowledge creation: Socialization, Externalization, Combination, and Internalization. Tacit knowledge is shared through Socialization, which is then articulated into explicit knowledge during Externalization. The explicit knowledge can then be further synthesized and organized in Combination and finally absorbed into individuals’ tacit knowledge through Internalization. This cyclical process creates a “knowledge spiral,” enabling the ongoing creation and sharing of knowledge within and beyond an organization. The diagram that illustrates the four processes can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Four stages of the SECI Model (Nonaka et al., 2000)

Let me elaborate on how I implemented the SECI model to facilitate the knowledge creation process based on the veteran teacher who excels in creating a supportive atmosphere during the PSTC:

- Socialization: tacit knowledge is shared through direct interaction and observation. Parents who have experienced the PSTC conducted by the veteran teacher were interviewed to understand their feelings about the conference, including how the teacher created a supportive atmosphere, the data shared, and the communication style used. I also shadowed the veteran teacher during the next PSTC to directly experience the atmosphere, observe the conversation, and take detailed notes on the teacher’s approach and methods.

- Externalization: the tacit knowledge observed in the socialization phase was articulated and documented. I compiled the insights gathered from interviews with parents and observations that I did on the veteran teacher. Based on this, the veteran teacher was then invited to share their strategies, tips, and thought processes for conducting clear and supportive PSTCs during a divisional meeting.

- Combination: Other teachers were also invited to share their experiences and strategies for creating conducive PSTCs during the meeting. These inputs, combined with the veteran teacher’s methods and parent feedback, were then compiled into a set of descriptors or guidelines for conducting an effective PSTC. The rubrics were then stored in the school’s online domain as a shared document accessible to all teachers.

- Internalization: the descriptors were then made as an official guideline for teachers to use during the PSTC. Each teacher should follow the combined explicit knowledge in the descriptors and transform it into tacit knowledge in the form of skills for conducting effective PSTC. As the teachers implement the rubrics, they will receive feedback from parents and students, as well as engage in self-reflection, which will further develop their tacit knowledge and skills in conducting PSTC. This process will enable ongoing knowledge creation to improve the school’s PSTC over time.

The Leaders’ Role and Further Impact of the SECI Model on School Culture

The SECI model can be used as a framework to shape the school culture. Conversations and interactions among staff in schools can have both positive and negative effects, depending on the nature of the interactions. While positive interactions build trust and foster collaboration, negative conversations, such as gossip, can damage relationships and create a toxic environment. EntreLeadership (2024) states, “Gossip is a cancer. It will destroy your team. It will destroy your organization.” Charles Duhigg (2012), in his book The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, explains that the most effective way to eliminate a bad habit is not by forcing people to avoid it but by replacing it with a good habit. Therefore, understanding the SECI model may help staff to engage in meaningful conversations centered on reflections, evaluations, ideas, and innovations during their time together, such as collaborative meetings or informal conversations in the faculty lounge.

In his book Leading Change (1996), John Kotter emphasizes the critical role leaders play in driving change within organizations. “The entire guiding team needs to be a role model for the behavior expected of employees during the transformation. That is especially true of the leadership” he states. Therefore, it is not enough for us as leaders to share and use the SECI model in formal structures, such as meetings; it must be embedded in our mental models, shaping our behaviors and expressions during interactions with staff to inspire them to follow suit. For example, when a teacher shares a new teaching approach that works well in their class, acknowledge their effort and share the idea with other teachers during a faculty meeting or through an internal communication platform.

Summary

Imagine if, as a leader, you could bring together the inspiring tacit knowledge of all stakeholders in your school. By doing so, you would be able to continuously accumulate knowledge assets in your effort to establish your school as a learning organization. Senge (1995) emphasized that when an organization becomes a learning organization, it can improve its adaptability, innovation, and competitiveness. Additionally, as members of a wider educational organization, such as LYIS, we can collaborate during the combination stage by pooling the explicit knowledge accumulated in our schools. This shared knowledge can then support each school in building its knowledge assets, ultimately helping our young people thrive and preparing them to face any future challenges while creating a better world for themselves and others.

Thank you for reading.

Reference:

Duhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House Trade Paperbacks.

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading Change. Harvard Business Review Press.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(99)00115-6

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press.

EntreLeadership. (2024, November 7). Gossip is Poison to Your Team. Ramsey Solutions. https://www.ramseysolutions.com/business/gossip-is-poison-to-your-team?srsltid=AfmBOopboySHmisAUpzx9QemwWFl4gxcx2zwACwwGfo8YUmllWV_rx_W

Senge, P. M. (1995). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday/Currency.

Alissa Gouw is Head of Secondary, Deputy Head of School, International School of Dongguan

Next week’s Principal’s Blog is written by Gavin Kinch, Principal, ACS International Singapore

Alissa will be delivering a workshop on the SECI Model at #LYIS25. The conference takes place from the 28th to 30th March at Foshan EtonHouse International School (FEIS). To join her, click here: https://forms.gle/YCJsFQByeuTbMbqv9