by Marcelle van Leenen

Do you have an excellent EAL specialist at your school? They might be your next principal!

My journey in education began in an International Baccalaureate (IB) school, where I served as an English teacher and Head of EAL (English as an Additional Language). This role ignited a passion for language and literacy in multilingual contexts, setting me on a path that I’ve continued to follow throughout my professional life. The journey was personal for me, given my own background as someone born in the UK to Dutch parents and raised internationally. It was only through my work in EAL and working in an international school that I came to fully understand and appreciate the richness of being bilingual.

As my career progressed, I continued to work in areas related to EAL, Literacy, and Digital Literacy, and also as a Primary Homeroom teacher. It was during my time as a Primary Homeroom teacher that I was fortunate to collaborate with a qualified and highly skilled EAL teacher, Helen Absalom, who shared my background and understanding of teaching, learning and language. I consider these my most successful years in teaching. Our approach was rooted in considering language and accessibility at every turn. We asked ourselves: Can our learners access this content? Are their identities represented in this book? What language will they have to use for this task? How can they use their home language to create meaning? What structures can we put in place to practise new language skills and vocabulary? Are they using enough ‘talk for learning’? In which language will they present their work? What do they need to know about multilingualism and their bilingual brains to help them learn? What connections can be made between their languages? In our class, students were made to feel successful. Our approach was as much about language and literacy as it was about embracing the diverse linguistic and cultural identities of our learners.

Unearthing Biases in Language and Education

Effective language and literacy practices in an international school extend far beyond just teaching; they encompass social mobility, inclusion, diversity and equity. Nonetheless, it can be disheartening to notice that English as an Additional Language (EAL) often still suffers from a stigma of being less esteemed compared to other subjects. Perhaps this is because historically some schools’ language policies were very ‘English only’ focused and EAL was seen as a deficit, leading to the implementation of isolated “pull-out” programmes that lacked integration with regular classroom instruction. Consequently, learners who returned from such programmes often found themselves inadequately prepared to access the standard curriculum.

Unfortunately, the position itself has sometimes attracted individuals who may not possess a genuine interest in teaching or the requisite skills. As a result, there have been instances where individuals considered less effective in teaching have been assigned to the EAL role, with the belief that they might cause the least damage there.

In an effort to unearth these biases and challenge them, one of the things I explore in workshops I lead for the IB on the Role of Language are statements that conceal biases. These statements may include:

– At a curriculum planning meeting: “Helping out” EAL learners – because they won’t be able to do this! Why equate language with understanding?

– A teacher to a student receiving EAL services: “Pay attention, because you want to exit EAL, don’t you?” Why should EAL be seen as a punishment?

– An administrator at a recruitment fair: “We don’t have anything for your husband, but perhaps he could do a bit of EAL?” Is he even qualified?

– A classroom teacher to an EAL specialist: “There is no way they can understand the unit of inquiry, so can you take them out for some survival English?” Why can’t they use their home language for learning?

– In a school policy: “The expectation is that all students, faculty, staff, and administration will use English as the primary language of communication, including for the purpose of social interaction, on campus.” Can you even call yourself an international school?

I sincerely hope that such biased statements are becoming less and less common in international schools and it is good to see more and more advocates, experts and thought leaders in this area such as Eowyn Chrisfield and Ruslana Westerlund.

The Multifaceted Role of an EAL Specialist

The role of an EAL specialist extends far beyond these stereotypes and misconceptions. In reality, this role provides excellent preparation for the position of a school leader because it necessitates immersion in every aspect of a student’s educational experience.

- Lesson Design, Curriculum, and Instructional Strategies: Early in my career, I had to design curriculum and instructional strategies that catered to the diverse linguistic needs of students. The goal was to ensure that every child, regardless of their language background, had equal access to quality education.

- Holistic Approach: As an EAL specialist, I realised that success in education goes beyond the classroom. It’s about considering the broader picture. Both roles, as an EAL specialist and a school principal, require a holistic approach that takes into account not only academics but also the social, emotional, and cultural aspects of students’ lives.

- Relationship Building: Establishing trust and strong relationships with teachers, staff and students was crucial then and remains vital now. As a school principal, forging connections with staff, students, and parents creates a positive school culture and fosters collaboration.

- Professional Development: The need to provide teacher training and professional development is a shared responsibility. A principal, just as I did in my early career, ensures that educators are equipped with the skills and knowledge they need to support their students effectively. Through PD, they invest in modelling what should be happening in the classroom.

- Parent and Community Engagement: Whether it involves organising parent education sessions or advocating for the school’s mission or multilingualism, both an EAL specialist and a school principal build strong bridges between the school and its stakeholders.

- Advocacy: Advocating for a vision and values is a common thread. I became an advocate for multilingualism in the school and in the wider educational community. Similarly, a school principal advocates for the school’s mission, educational goals, and student success. Both roles require leadership in advancing a particular vision.

- Structures and Systems: These encompass the organisation and policies within a school. A principal ensures that structures and systems support the diverse needs of students, including those who are multilingual. This can involve curriculum planning, resource allocation, and language policies that create an inclusive learning environment.

A Journey from Language and Literacy to Leadership

In reflection, I realise that my early experiences and roles in leading language and literacy in schools, with a focus on multilingual contexts, were invaluable in shaping my abilities as a school leader. Ensuring the success of multilingual learners must be approached holistically, just as I did in my earlier roles. It’s about more than what happens in the classroom; it’s about creating a supportive ecosystem where every student has the opportunity to thrive, regardless of their linguistic background.

Given my passion for international education, the opportunity to transition into a leadership role and have a meaningful impact in line with my values and vision was a welcome one. My first role as a school principal was in a school with a French/English bilingual program. With such a programme, the school matched my values and vision, but even there, there was plenty of professional learning to be done about language and learning and how to provide bilingual education most effectively. We had to develop a shared pedagogy, a transdisciplinary approach, and ensure the language model aligned with the context of the PYP (Primary Years Programme).

These shared skills and experiences underline the idea that school leadership, especially in diverse and multilingual contexts, demands a deep understanding of how to create an inclusive, supportive, and effective learning environment. My journey from working directly with multilingual learners to leading an educational institution has shown me that the principles of effective leadership transcend specific roles and contexts. It’s about recognizing the power of education to transform lives and being committed to making that transformation accessible to all students, regardless of their linguistic or cultural background.

Marcelle van Leenen is Primary School Principal at Windhoek International School, Namibia. She is an IB Workshop and School Evaluation Leader and is a member of The International School Literacy Collaborative, helping schools develop effective language and literacy programmes in multilingual contexts.

To connect with Marcelle on LinkedIn, click Here

LYIS is proud to partner with TIC Recruitment

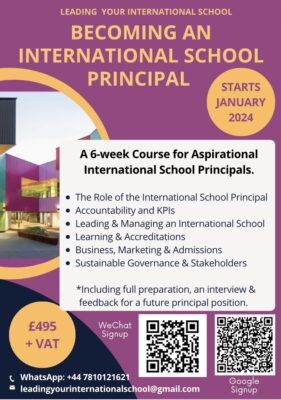

If you are considering becoming an International School Principal, then why not sign up for our course in January – ‘Becoming an International School Principal’.

Thank you Marcelle for this enlightening and thought-provoking piece. There are many reasons why EAL teachers are likely to make good leaders and I resonate with your arguments surrounding curriculum design and a holistic approach. So often the EAL teachers I’ve come across are calm heads, incredibly resilient, and able to integrate students with a moment’s notice.

Thank you André, and yes, I agree EAL teachers are often calm, resilient and resourceful. Good ones think on their feet, slotting in whenever they can, and they work very hard on building relationships with teachers for the benefit of multilingual learners. They support learners, but at the same time they have to convince teachers that co-teaching is beneficial as well as sometimes challenge misconceptions about language learning.